I like Westerns. Every generation has an inherited nostalgia for the times before they were born; kids these days wear Nirvana t-shirts and my parents' generation liked World War 2 movies. But there is a "best by" date on pop culture and eventually every fashion gets reinterpreted until it fades into irrelevance. I may like Westerns, but they are dying out.

Tales from the Western frontier were always popular in America. Gunslingers and Lawmen were the heroes of the dime novel even when the frontier was still open, eagerly consumed by the people who had stayed back East. As that frontier began to close the American West passed into legend and by the 1950s there was a flood of TV shows and movies that glorified the victorious last stage of pioneering America. While men were riding rockets to the moon, kids were dressing up to play cowboys and indians. But the moon rockets soon stopped, and so did the country's love affair with the Wild West.

The past can never change, but History always changes with the culture. I was late to the party and my first Western movies were very different from the ones my parents watched as kids. Dances With Wolves was the Western epic of my childhood era and it was a sign of things to come; a hand wringing re-examination of American identity, a celebration of Native American nobility and a confession of national guilt.

Decades later, those themes have permeated American media to the point where they have become historical fact. American Westward expansion was an unforgiveable act of a savage culture, and the American Indian is a blameless victim deserving of our sympathy; so the story goes today.

The more ubiquitous that kind of story becomes, the more I find myself looking for entertainment that isn't constantly preaching from that pulpit. I sought the nostalgia of a different theme and followed the trail back from the Westerns of the modern era, to the days of John Wayne by way of Clint Eastwood. What I saw was an incremental change in values, as well as a steady evolution in the depiction of truth. Far from the current accusation that mid-century America was caught in a fever-dream of ignorance was the fact that the old John Wayne movies did advocate for the humanity of the American Indian. They just did it without the wholesale condemnation of the settlers. And perhaps most interesting of all, they presented the American Indian as an indomitable force of nature capable of brutally shocking violence.

With this alternate impression in mind, however unacceptable to modern sensibilities, I decided to find out just why there is such a discrepancy between the modern view of the Wild West and that which was widely accepted just two generations ago. I watched every Western I could get my hands on, and I sought out older documentaries and books about the Indians and their encounters with the new Americans. Two pivotal topics stood out; the complexities of the French and Indian War, and the ferocious back and forth between the early Texans and the great Comanche nation.

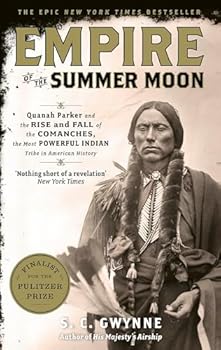

This book, while certainly written with a tone sympathetic to Native Americans, depicts them with the honesty that is lacking in today's culture. While the author is often critical of the American government's treatment of the Indians, he doesn't demonize the settlers or the forces of Westward expansion. The tone of those old Westerns makes sense in light of the explanations and reasons given in Empire of the Summer Moon and yet it reads with the excitement of a dime store novel. There are plenty of heroes and villains on both sides, desperate last stands, and best of all, fascinating insights into the past that strike beyond matters of identity and into the heart of humanity itself.

I will try to distill some of what I learned from this book, breaking things down into category topics, and marking the road traveled for anyone else who is interested not just in History, but what actually took place long ago, in the Wild West.

The title of the book, "The Empire of the Summer Moon," is a reference to the full moon and the terror it struck into the hearts of settlers. From the time of the Spanish colonization of America until the dawn of the 20th century, the full moon was also called the Comanche Moon because when it lit the night sky the Comanche would use it to navigate great distances in order to launch their raids. When the full moon was up, no enemy was safe no matter how far away from the front lines of Comanche territory.

At its peak, that territory covered much of what is now Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico and Texas, down even into Mexico. The Comanche didn't always control such a large territory nor were they native to the area; they split off from the Shoshone people further up in the Rockies, likely pushed out from competition or lack of resources. But when the Comanche came down into the Plains they made the most of the region's greatest resource; the horse.

The Spanish Mustang was bred for the rugged, dry regions of Spain and was therefore uniquely suited for life on the American plains. As the Spaniard's horses escaped, or were abandoned due to wars or lost settlements, they formed large wild herds roaming the same areas as the American Bison. Many Indian nations learned to domesticate the Mustang, but no one mastered the art as well as the Comanche.

The Comanche were expert and adept horsemen in all ways. Unlike most of the other Plains Indians, the Comanche took great care in selectively breeding their own horses. They improved their own stock over time. They also had a method for quickly breaking the wild horses they captured. After capturing a wild Mustang they would choke the horse near to death and then breathe into it's nostrils, both aiding the horse and establishing dominance. Quick and effective.

A young Comanche brave would take responsibility for his own horse as young as six. By the time he was ready to go out on raids, he could sling himself to the side and under the neck of his mount and fire arrows from that position with his body protected from enemies. He could also fire as many as five to six arrows in rapid succession before the first would hit the ground, and his accuracy was severe enough to be able to hit a coin. While most of the other Plains Indians and all of the early settlers would dismount in order to fight, the Comanche fought almost entirely from horseback. No one could match their speed or rate of fire.

They practiced no agriculture and made no permanent settlements, migrating across their territory as they followed the Bison. Their religious culture was not as developed as other Indians and their social structure rivaled the ancient Spartans of Greece in its martial simplicity. In order to support this extreme emphasis on warrior culture, the gender gap in Commanche society was stark. The men did no work, and even the boys had no chores, as they were expected to be training for war first, foremost and always. The women bore the entire responsibility for camp tasks, putting up and taking down the tipis, chopping wood and butchering the Bison meat and tanning the hides. Sometimes, when white female captives were encountered in Comanche camps, they indistiguishable from Comanche women due to all of them being stained in the blood and offal of Bison.

The brutality of Comanche life guaranteed their dominance. For centuries, no other group could challenge them in combat, not even the white man with his superior technology. No one could travel as far and as light as the Comanche, and absolutely no one could stand up to them in a fight. While they could raid hundreds of miles away from their camps, no one left their territory, the Llano Estacado (the Staked Plains), alive. They raided with impunity. When pursued into the high plains, they would wait until nightfall and steal the horses of their pursuers, leaving them stranded to die of exposure or lack of water.

On the American Plains, the Empire of the Summer Moon not only rivaled, but exceeded those of the Spanish, Mexicans, Texans and Americans for hundreds of years.

Learning about the conflict between the American and Comanche Empires